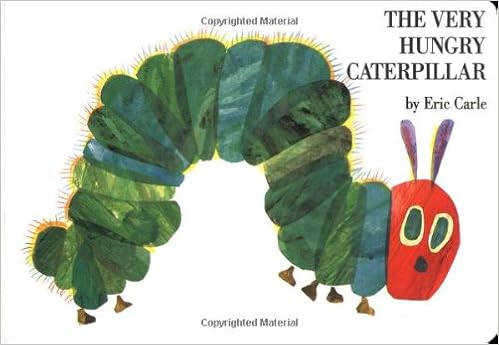

![The Fault in Our Stars by [Green, John]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51dezgvr%2B7L.jpg)

(Photo courtesy of Amazon.com)

Summary: Hazel is a 17 year-old girl who is battling thyroid cancer, and her mother has decided to have her to go to a cancer patient's group for therapy. As much as she is reluctant to go, she complies. While there, she meets a boy, Augustus Waters who is now in remission after having his leg amputated because of osteosarcoma. The two are able to kindle a friendship, and they build a relationship. Hazel asks Augustus to read a book, An Imperial Affliction. She explains how the author, Peter Van Houton, fled to Amsterdam shortly after the books success. Augustus is able to track down the assistant, Liedwij, to Houton. This opens up a correspondence via e-mail between Hazel and Houton. He invites her to visit him should she ever find herself in Amsterdam. This gets the wheels rolling to get Hazel to meet this reclusive author. Who else could possibly manage to get her to Amsterdam but Augustus, who has used his charitable foundation wish to grant Hazel hers. And he does it in a very romantically themed Dutch picnic. What will happen on her trip? Will she get her answers about the young girl suffering from cancer in the novel?

APA: Green, J. (2012). The fault in our stars. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Review: This is easily one of the biggest titles of the year — six starred reviews! Big time buzz! John Green! Previous Printz winner! Nerdfighters! — so we’ve been thinking about it for a while. Since this is a book from a former Printz winner and honoree, we knew we’d be reading it with our Printz glasses on. When you add the serious subject matter, the thoughtful treatment of said subject matter, the memorable characters, and the five-hanky tear-jerker of a plot, you know there’s a lot to talk about in terms of Printz-worthiness.

Hazel has terminal cancer. Augustus is a cancer survivor who has lost a leg to the disease. They meet in a teen cancer support group. It’s complicated and baggage-filled love almost at first sight. She doesn’t want to die on him; he wants to save everyone. It’s clearly a recipe for heartbreaking disaster. Their mutual love of (fictional) Peter Van Hauten’s (fictional) An Imperial Affliction gives the two an excuse for a road trip, but plot happens and PLOT PLOT PLOT.

When you read a John Green book, you know that the writing is going to be shiny and sharp. The dialogue will be rapid-fire and dramatically intelligent. Fault does not disappoint. Augustus and Hazel engage in electrifying debates (he fears oblivion; she choses to ignore it) and hilarious reparte (“The day of the existentially fraught free throws was coincidentally also my last day of dual leggedness,” Augustus says).

Actually, that second quote is pretty magnificent: intelligent, wry, but wrapped in sadness. Gus, Hazel, their friend Isaac: all of them casually shrug off Cancer Perks (trips to Disneyland, autographed basketballs) while attempting to grapple with the pitfalls of teenagerdom and, you know, also mortality. The teen characters are smart, funny, and determined to maintain their dignity and kindness. Hazel describes the horrible awareness kids with cancer have: “There is only one thing in this world shittier than biting it from cancer when you’re sixteen, and that’s having a kid who bites it from cancer.”

Green’s depiction of friendship is dead-on (as usual, although of course that has nothing to do with Printz conversation). Hazel, Gus, and Isaac, as a threesome, are sarcastic, honest, and loving with each other. Minor characters, like Gus’s parents and Hazel’s friend Kaitlyn, have very limited page time, but are still memorable and well drawn. This is a teen book with really (like, really) fantastic parental characterization.

Hazel and Augustus’s weighty conversations and observations allow Green to weave many themes together. The idea in the title, the fault in our stars, the harmatia that lives in all of us shows up in so many different ways and through different images (people as grenades; broken, drunk and abusive Van Hauten; cancer itself) and doesn’t feel forced or false. There is a lot in this book to love.

Unfortunately, there is a problem. Van Houten, the author of An Imperial Affliction, the person Gus and Hazel travel to Amsterdam to see, comes back for the [REDACTED EVENT, in case you live under a rock, but know that comments are fair game for spoilers]. So much weaksauce. Early on in the novel, Hazel tries to describe her love for An Imperial Affliction:

“But it’s not a cancer book, because cancer books suck. Like, in cancer books, the cancer person starts a charity that raises money to fight cancer, right? And this commitment to charity reminds the cancer person of the essential goodness of humanity and makes him/her feel loved and encouraged because s/he will leave a cancer curing legacy.”

But the decision to bring Van Hauten back makes this book suddenly feel like A Cancer Book — full of lessons and realizations and Important Character Growth. It’s cliche and I believe it severely weakens the integrity of the book.

I still cried, believe me. The eulogies on command scene? Tears. The last letter at the end? Tears. This book is powerful, strongly written, and has so much good stuff going on. But Van Hauten’s reappearance occurs at a crucial moment in the book, and feels too pat and perfect. It changes Fault from something that is transforming the cliches of a cancer book into a Cancer Book. Printz winners are books that move beyond what we expect, and the Van Hautening has the opposite effect.

However, there is so much good in this book, so much that is extraordinary. Is the flaw forgivable? Is that small portion of the plot forgivable? Oh, to be a fly on the wall of the Printz room!

Citation: Couri, S. "You may have noticed John Green wrote a book this year." School Librarians Journal. Retrieved from http://blogs.slj.com/printzblog/2012/09/16/you-may-have-noticed-that-john-green-wrote-a-book-this-year/

Library Use: This book shows how people deal with grief, friends, families, boyfriends/girlfriends. It deals with disappointment, sadness, loss, and upset, but it also shows how to enjoy life no matter what it offers.